The Commission owes its existence to the vision and determination of one man – Sir Fabian Ware. Neither a soldier nor a politician, Ware was nevertheless well placed to respond to the public’s reaction to the enormous losses in the war. At 45 years of age, he was too old to fight but he became the commander of a mobile unit of the British Red Cross. Saddened by the sheer number of casualties, he felt driven to find a way to ensure the final resting places of the dead would not be lost forever. His vision chimed with the times.

Under his dynamic leadership, his unit began recording and caring for all the graves they could find. By 1915, their work was given official recognition by the War Office and incorporated into the British Army as the Graves Registration Commission.

Ware was keen that the spirit of Imperial cooperation evident in the war was reflected in the work of his organisation. Encouraged by the Prince of Wales, he submitted a memorandum to the Imperial War Conference.

The Imperial War Graves Commission was established under Royal Charter dated 21 May 1917 from King George V, on the recommendation of Edward, Prince of Wales. The purpose and powers of the Commission are detailed in the Charter. The Commission included statutory representatives as well as representatives of the Governments of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland. The first president was the Prince of Wales.

The Commission’s work began in earnest after the Armistice. Once land for cemeteries and memorials had been guaranteed, the enormous task of recording the details of the dead began. By 1918, some 587,000 graves had been identified and a further 559,000 casualties were registered as having no known grave.

Today, not all of those who are recorded as being buried in a particular war cemetery have a headstone and are instead remembered on memorial walls.

The Commission set the highest standards for all its work. Three of the most eminent architects of the day – Sir Edwin Lutyens, Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Reginald Blomfield – were chosen to begin the work of designing and constructing the cemeteries and memorials. Rudyard Kipling was tasked, as literary advisor, with advising on inscriptions.

Ware asked Sir Frederic Kenyon, the Director of the British Museum, to interpret the differing approaches of the principal architects. The report he presented to the Commission in November 1918 emphasised equality as the core ideology, outlining the principles we abide by today.

The largest Commonwealth War cemetery is the Tyne Cot cemetery in Belgium containing about 12,000 headstones. Possibly the smallest is at Ocracoke Island, North Carolina USA where four Commonwealth sailors lie.

Today, a century later, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission honours the 1.7 million men and women of the forces of the Commonwealth who died in the two world wars and ensures that their memory is never forgotten.

The organisation cares for cemeteries and memorials at 23,000 locations in 154 countries. Its values and aims, laid out in 1917, are as relevant now as they were almost 100 years ago.

The Commission’s principles include:

- Each of the dead should be commemorated by name on the headstone or memorial

- Headstones and memorials should be permanent

- Headstones should be uniform

- There should be no distinction made on account of military or civil rank, race or creed

http://www.cwgc.org/about-us.aspx

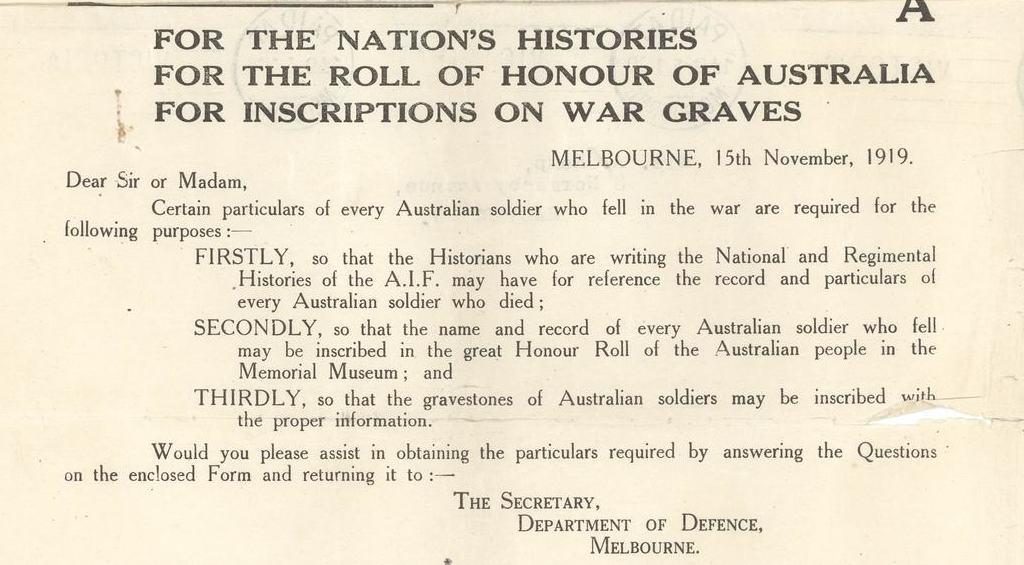

In Australia, a letter dated 15 November 1919 signed by the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Home and Territories, was sent to relatives of Australians who had died in World War One.

The letter requested information For the Nation’s Histories; and For the Roll of Honour of Australia.

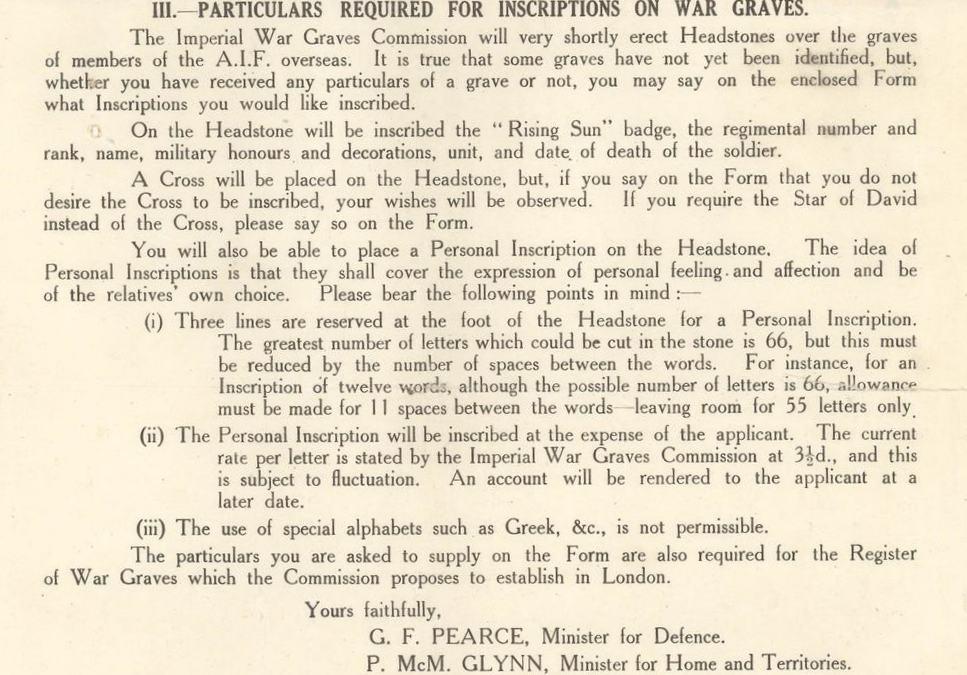

The letter also requested information to assist with the erection of headstones on graves of members of the AIF overseas and the establishment of a Register of War Graves in London. It described the process for the erection of headstones over graves of members of the AIF overseas and offered relatives the option of having personal inscriptions included at a cost of 3½d per letter and a maximum of around 55 letters.

Source: Collection, Museum Victoria 418904